Tens of thousands of years ago, Kauri forests dominated northern New Zealand. Some giants stood over 50 metres tall and lived for more than 2,000 years. Massive earthquakes and tsunamis toppled these trees, in some cases burying 100-tonne logs upright in deep swamps. Oxygen-starved mud preserved them perfectly for up to 50,000 years.

For millennia, these buried giants lay hidden while human civilisation rose elsewhere. By the time Māori arrived in the 13th century, the living kauri forests still stretched unbroken across the north.

Ai representation of how kauri tree were sunk and how ancient swamp kauri gum (amber) was preserved.

To Māori, kauri was both sacred and practical, used for waka taua (war canoes), carvings, and gum for fuel and sealing adhesive. They took only what was needed.

From the 1800s, European settlers felled kauri on a massive scale for shipbuilding, housing, and export. Swamps were drained to dig up buried logs, and the timber was shipped worldwide, even used to help rebuild London after the Great Fire.

By the early 20th century, most giant kauri were gone. Today, living ancient trees are legally protected, but the swamps still yield “subfossil” kauri, a timber so rare and beautiful it is now reserved for art, heirloom furniture, and jewelery, each piece holding a story older than civilization

Kauri gum exports peaked around 1900 and declined through the 20th century as markets changed and synthetics replaced natural resin.”

“Export volumes soared from a few hundred tonnes in the 1850s to over 11,000 tons in 1900, then

Industrial kauri deforestation and gum digging are directly linked. From the mid-1800s to early 1900s, massive areas of Northland kauri forest were logged or burned for timber, ships, housing, and export. When kauri were damaged or felled, resin flooded into the surrounding soil, creating vast under-1000-year-old gum fields across cleared land. This triggered the first gum rush.

In the kauri industrial era, nearly all felling was done by hand. Two-man crosscut saws and long pit saws brought down trees that could exceed 40 metres in height and several metres in diameter. There were no engines in the bush only muscle. Bullock (cow) teams provided the power, hauling immense kauri logs on wooden skids and tramways. Progress was slow, brutal, and precise; every log moved represented weeks of human labour and animal strength.

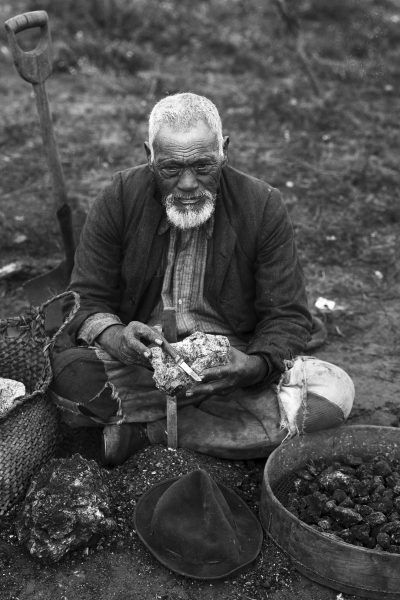

By the late 1800s, kauri gum was one of New Zealand’s top exports, with 8,000–11,000 tonnes dug annually at its peak, mostly from shallow ground. Gum prices varied wildly depending on quality, but commonly ranged from £30 to £80 per ton, with top-grade clear gum fetching even more. Tens of thousands of people, Māori, settlers, Dalmatian migrants, relied on gum digging as a hard, dangerous survival economy.

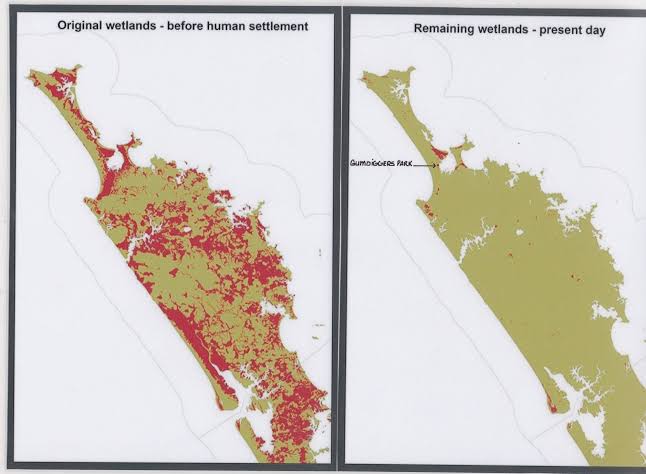

As surface gum ran out, diggers went deeper and older. The second wave of gum digging moved into swamps and wetlands, uncovering ancient kauri gum and timber buried by natural disasters long before humans arrived. Geological evidence shows multiple large flooding and tsunami events flattened prehistoric kauri forests, burying resin and logs under silt where they fossilised.

This material ranges from 3,000 to over 50,000+ years old, often found alongside swamp kauri timber. Unlike younger forestry gum, this was true kauri amber harder, darker, rarer, and far more valuable. By the early 1900s, most remaining gum production came from these deep swamp deposits, marking the shift from industrial resource scraping to the extraction of deep-time natural artefacts formed by catastrophe, not chainsaws.

where to find kauri gum

Kauri gum is found where ancient kauri forests once stood. The old gum-digging fields of Northland are the classic sources, especially flat, low-lying ground near sea level where resin accumulated and was buried over thousands of years. Gum also appears in streams, creeks, and rivers where erosion re-exposes it, and after landslides that cut into old forest soils. Beaches and lakes can yield rolled gum washed out from inland deposits, but the richest finds were usually deep underground on flat country, sealed and preserved from

Scientific Insights

Kauri Gum Facts and FAQ

Check us out on TikTok