Tens of thousands of years ago, kauri forests dominated northern New Zealand. Some giants stood over 50 metres tall and lived for more than 2,000 years. Massive earthquakes and tsunamis toppled these trees, in some cases burying 100-tonne logs upright in deep swamps. Oxygen-starved mud preserved them perfectly for up to 50,000 years.

For millennia, these buried giants lay hidden while human civilisation rose elsewhere. By the time Māori arrived in the 13th century, the living kauri forests still stretched unbroken across the north.

To Māori, kauri was both sacred and practical — used for waka taua (war canoes), carvings, and gum for fuel and sealing adhesive. They took only what was needed.

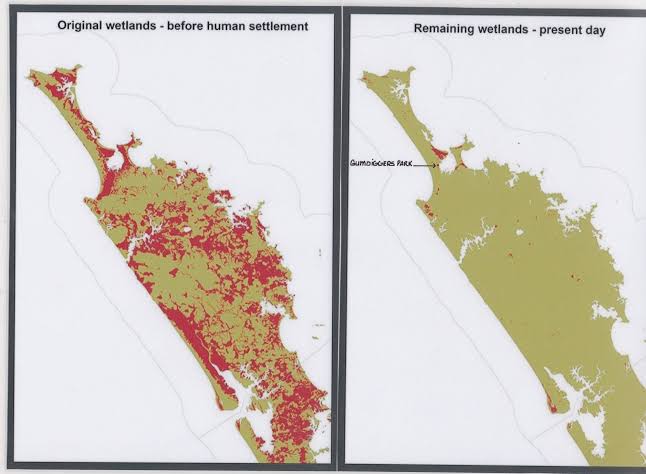

From the 1800s, European settlers felled kauri on a massive scale for shipbuilding, housing, and export. Swamps were drained to dig up buried logs, and the timber was shipped worldwide — even used to help rebuild London after the Great Fire.

By the early 20th century, most giant kauri were gone. Today, living ancient trees are legally protected, but the swamps still yield “subfossil” kauri — a timber so rare and beautiful it is now reserved for art, heirloom furniture, and jewelery, each piece holding a story older than civilization

Ai representation of how kauri tree were sunk and how ancient swamp kauri gum (amber) was preserved.

where to find kauri gum